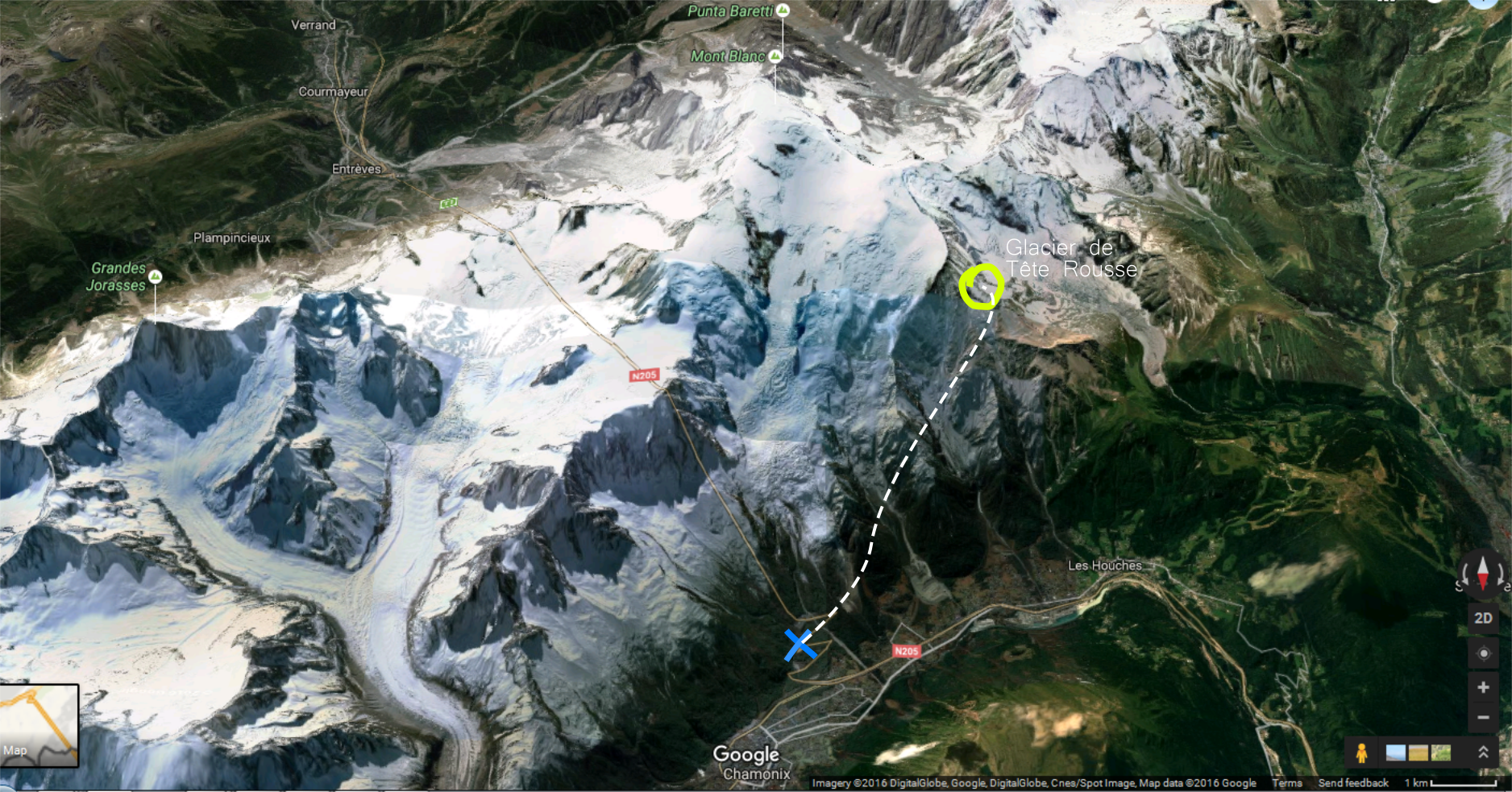

It’s 7:20 am, uphills of Chamonix in a 70x30m opening in the forest. The sun is rising behind the mountains in front of us but can’t be seen just yet. The steep slopes of the Massif du Mont Blanc are in the way, all around, peaking at 4800 m some 10km from here. We are ready with our gear, waiting for our transport to the Glacier de Tete Rousse, just below the Dome du Gouter.

A few minutes and radio messages later, the wild Squirrel aka Eurocopter Ecureuil appears above the trees and makes its approach into the tight landing spot. At the commands, with some 200 flight hours behing his belt, the son of the company chief pilot and owner.

The previous evening, I was instructed by my colleagues to never walk behind the aircraft and to always let the heli land next to you without moving. I have no problem with that whatsoever!

Sure enough, the heli, stamped with a massive pinup decal, lands almost onto us as we kneel in the wind in the tiny space between us and a mobile fuel container. I’m in Apocalypse now, just without the fighting!

The engineer opens the cargo compartment, we scramble our gear inside and in less than a minute, we are on our way into the massive mountain.

It only takes about four or five minutes and about 2 vertical kilometers to get to the final destination, at 3200m.

As we approach, the instructor ask us where we want to get off, so we point him a spot next to the top of the glacier. With the front of the skids resting on the solid snow, the pilot keeps the aircraft in a hover and we rush out the heli, pick up the gear and get as flat as we can on the ground to let the crew get on with their next mission. 45 seconds flat touchdown to takeoff and they are back in the air diving back into the valley with what seems like a 45 degree angle. It only really occured to me after seeing it first hand, but these guy’s skills and responsibility are pretty insane, especially in such hostile environments. And here we’re only talking no wind and clear sky…

The glacier itself has a varying depth of ice base and surface snow, about 70m deep in the center. The subject of study: a water cavity containing possibly tens of thousands of cubic meters of water that need to be monitored because of the possible hazards in case of a rupture.

After finishing all the survey tasks around 1pm, it is time to get back down. A few unsuccessful radio messages indicate the pilots are on their lunch break. At this point, the weather starts to act capriciously. One minute it’s clear, a minute later clouds are creeping up the slopes reducing visibility to a few hundred metres.

An hour or so later, radio traffic picks up again on the frequency, talking about heli lifts, paragliders getting in the way of pilots, and other semi-intelligible chatter. At one point, we hear “montée tete rousse”. That’s us. A few minutes later indeed, the familiar heli appears from behind the northern ridge and lands with skids just about 2 meters from us in the now mellow snow. This time, a senior pilot is at the controls and expedites the dive back to the valley. We are smoothly stroming down. Speed : 120 knots, pitch about 15+ nose down.

After pulling a bit of G in the final right hand turn towards the landing zone, it strikes me how little foreward and down visibility over the instrument panel there is when flaring. We land with the cabin ~ 1,5m from metal fuel box thing, the pilot visibly having to make many small corrections to keep everything straight, probably due to some ground effects.

After a lightning fast drop-off turnaroud, the mountain cowboys dissapear behind the trees, into the clouds…